This is Part II of Arcus’s research series to guide organizations on strategic business scenarios post-Covid-19.

A global pandemic of this scale was inevitable. In recent years, hundreds of health experts have written books, white papers, and op-eds warning of the possibility.

Bill Gates has been telling anyone who would listen, including the 18 million viewers of his TED Talk. In 2018, many stories such as this one argued that the world was not ready for the pandemic that would eventually come.

In October, the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security war-gamed what might happen if a new coronavirus swept the globe. And then one did. Hypotheticals became reality. “What if?” became “Now what? First, the world needs to understand how this virus originated and how to contain it.

The virus

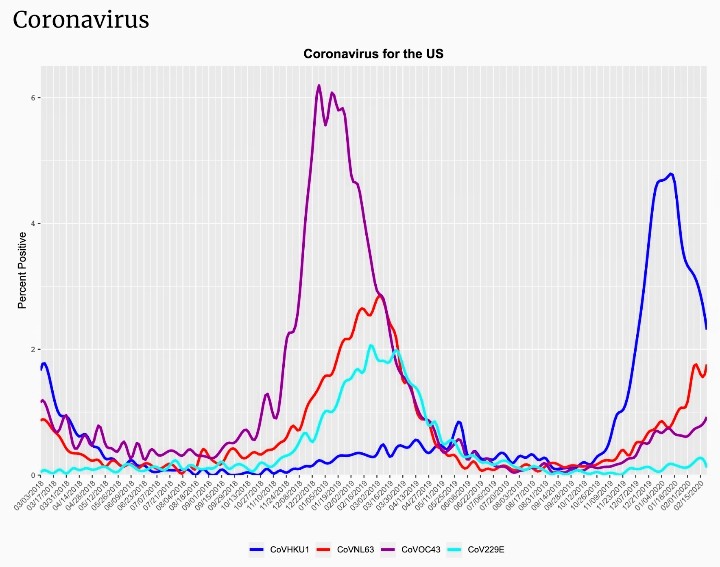

SARS-CoV-2 is the seventh coronavirus known to infect humans; SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 can cause severe disease, whereas HKU1, NL63, OC43 and 229E are associated with mild symptoms.

Scientists believe the direct ancestor of the coronavirus now known as SARS-CoV-2 has lived for so long in bats and other animals that it is no longer capable of making them sick. At some point near the end of 2019, the virus’s genetic code mutated in a way that allowed it to jump from its animal “reservoir” to its first human host.

At the time that leap was made, the virus had recently developed — or soon would develop — the ability to spread easily from human to human. The result is a global pandemic that has sickened at least 3.9 million people and caused more than 274,000 deaths.

The bad news is that COVID-19 is not going to be contained globally. The decent news is that some countries have done some things correctly to slow the spread of the disease for this Season.

Hindsight will be 20/20 on this one and there will have been mistakes made, however, in our opinion, slowing COVID-19 will eventually be found to have been impossible.

Why? Basically, three reasons for such a fast spread:

1) The COVID-19 infection life cycle could last for 4-5 weeks including a 2-week incubation period. So patients have COVID-19 for longer than other infectious diseases and are asymptomatic and yet contagious for longer. Hence, the 14-day quarantine model being used. However, there have been cases where individuals have been asymptomatic for up to a month. So is 14 days effective? Yes, as a short-term containment strategy but not as a long-term solution.

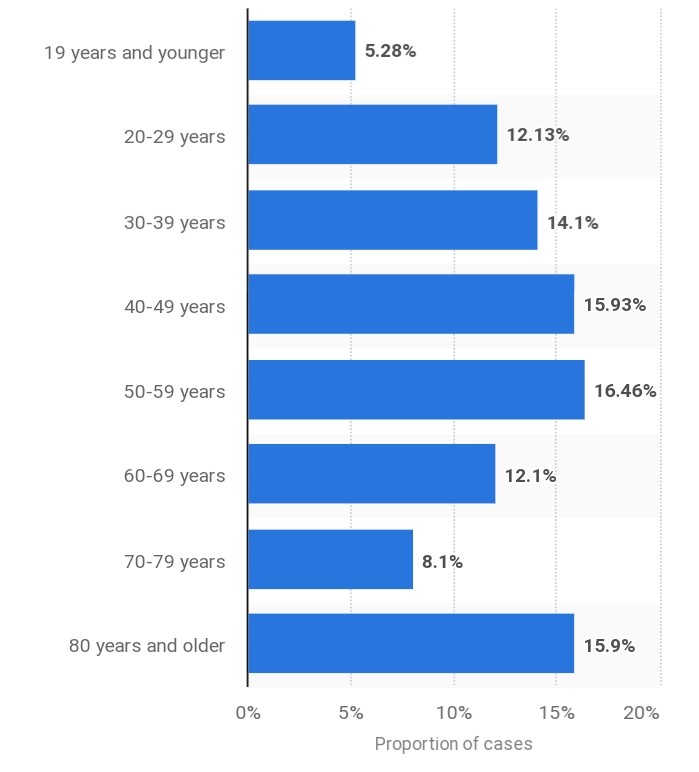

2) Initial data shows that 80% of people get a mild to moderate illness, about 15% of people experience a severe illness and 5% get labelled critical. Hence, there are people sick but not sick enough to avoid others.

3) Countries such as Spain, Singapore and South Korea have seen a surge of cases soon after reopening their economies.

Hope is not a strategy, a realistic outlook matters.

In the months ahead, the most important variable for business and government will be containment of the spread of the coronavirus and progress on potential treatments or a vaccine. As JPMorgan’s John Normand outlined in a note published earlier this month, the emerging dominant narrative is “starting to latch onto rapid development of COVID-19 therapeutics and hopes for a vaccine, and therefore fewer public health risks to reopening economies and a quicker return to normalcy.”

When will this end?

A lot depends on how well the virus is contained. A better question might be: “How will we know when to reopen the country?” In an American Enterprise Institute report, Scott Gottlieb, Caitlin Rivers, Mark B. McClellan, Lauren Silvis and Crystal Watson staked out four goal posts for recovery: Hospitals must be able to safely treat all patients requiring hospitalization, without resorting to crisis standards of care; the government (1) needs to be able to at least test everyone who has symptoms; (2) is able to conduct monitoring of confirmed cases and contacts; and (3) there must be a sustained reduction in cases for at least 14 days.

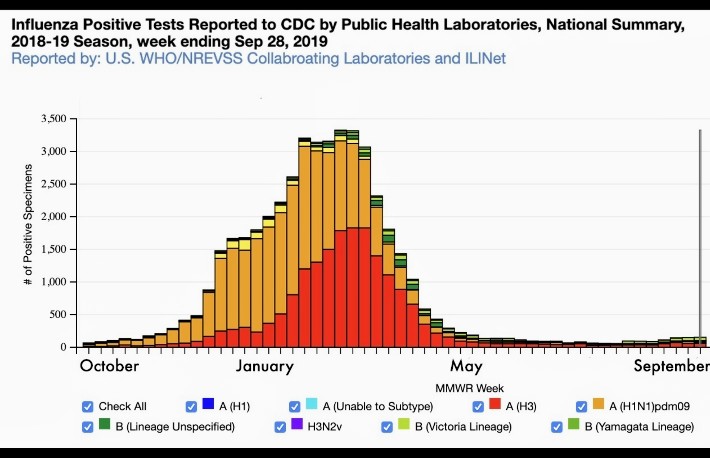

Let’s first look at the 2018-19 Flu Season:

Adapted from: National, Regional, and State Level Outpatient Illness and Viral Surveillance

First, notice, the “Flu” is really a number of different types of Influenza with (2) major types for last year. The Flu Shot you may elect to get each year usually has the 3 or 4 most likely flu variants or types most likely to cause the flu illnesses that next season. While the ‘effectiveness’ of the flu shot bounces between 20% and 50% (2005-2018), millions of people likely do not get the flu or get a milder version of it because of the vaccine and transmission rates, overall, are slowed considerably. So, the above picture is a snapshot of a majority of Flu Seasons.

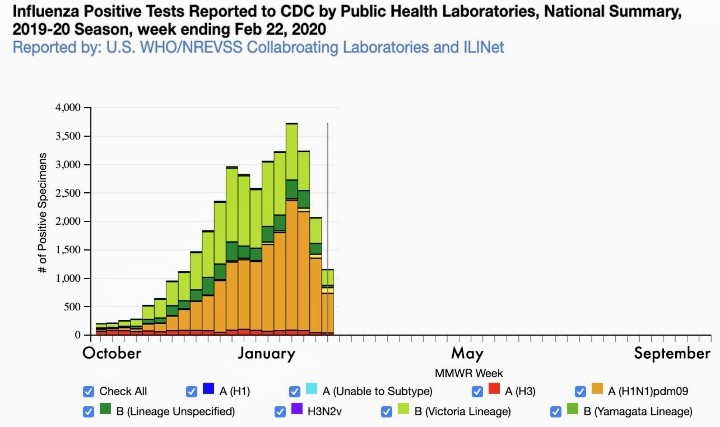

This year is likely to progress like the 2019-20 Season:

Adapted from: National, Regional, and State Level Outpatient Illness and Viral Surveillance

You see different colors in the bar graph for this year, a different curve and timing to the shape of the overall curve and basically, a different flu season compared to last year. We will all see how this cold and flu season ends but, in Arcus’s opinion, even flu infections are going to fall off sooner and faster than last year because many people are being safer (because of the COVID-19 outbreak and the news cycles about it) and maybe Spring will get here earlier next year.

COVID19 is at least similar in transmission to the Flu(s) we get in society and everything else being about the same, then you are very likely to get COVID-19 next season if you do not get it this year. But, there may be a vaccine.

Maybe, but it may also only be 50% effective. There may not be an effective vaccine, or not enough can be made and/or distributed and/or injected in time for next season, or a hundred other little issues with vaccines, rates of distributions, effectiveness and so, we just do not know what we do not know for next year.

Arcus’s conclusion is that COVID-19 will be a big part of next year’s colds around the world and in the United States and Canada but COVID-19 does not look much more deadly than the flu based on what’s been reported with a 1-3% morality rate in the general population but much higher (+10%) in older population groups with complex health conditions than the flu.

After that, assuming COVID-19 does not mutate in some manner and assuming most, 99.9%, of healthy humans, once they get COVID-19, form proper antibodies to COVID-19 and cannot get it again or there is a vaccine distributed, each new cold/flu season will see less and less beginning 2021-22. COVID19 will fade into history after that.

There is no ‘cure’ for the Cold & Flu Seasons on Earth, not yet.

The end game

A recent analysis from the University of Pennsylvania estimated that even if social-distancing measures can reduce infection rates by 95 percent, millions will still need intensive care which isn’t available at the scale it is required at this time.

First, a sustained and uniform worldwide effort is required. Every nation needs to simultaneously bring the virus to heel, as with the original SARS in 2003. Given how widespread the coronavirus pandemic is, and how badly many countries are faring, the odds of worldwide synchronous control seem vanishingly small. The competition rather can cooperation to develop a virus first and own the patent is an example of the lack of cooperation between countries.

Second, the only way to contain the virus long term is through herd immunization. The virus does what past flu pandemics have done: It burns through the world and leaves behind enough immune survivors that it eventually struggles to find viable hosts. This “herd immunity” scenario would be quick, and thus tempting. But it would also come at a terrible cost: SARS-CoV-2 is more transmissible and fatal than the flu in older populations, and it would likely leave behind a trail of devastated health systems. The United Kingdom initially seemed to consider this herd-immunity strategy, before backtracking when models revealed the dire consequences. The U.S. considered that approach too with disastrous consequences.

Social distancing works as a short term containment measure

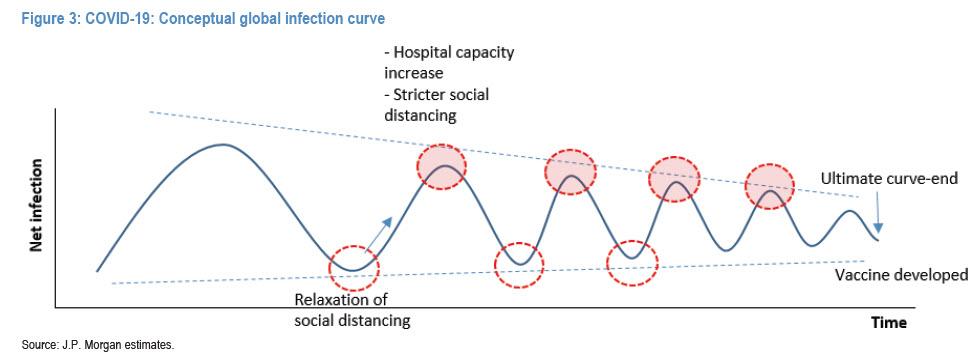

Reducing the susceptible (i.e., cutting new contacts) should remain the prime strategy. Herd immunity might be considered an option once a vaccine becomes available. However, there are concerns about a possible series of infection waves following relaxation of social distancing rules. Hence, based on epidemiology modelling frameworks, shortening the infection period (i.e., therapies: production of cytokine in COVID-19) and lowering the transmission rate (i.e., wearing masks) could be extra mitigating factors.

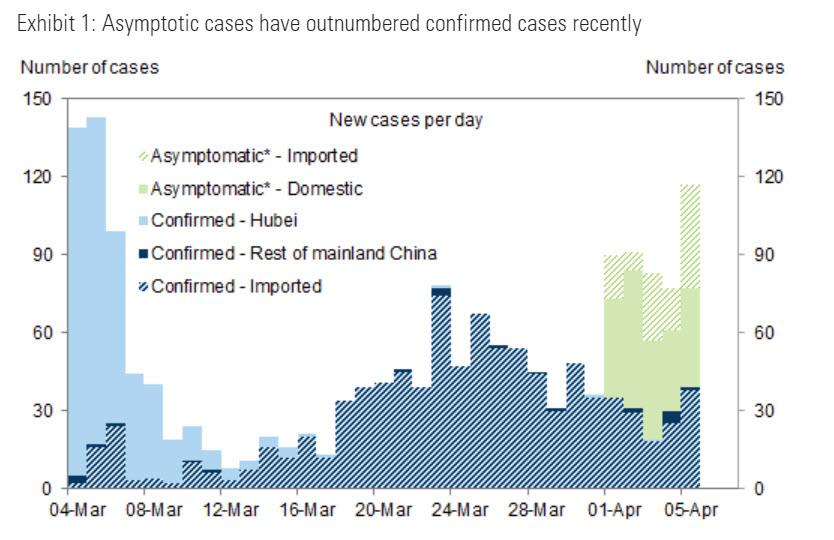

And speaking of the second wave of infections, there is some not so good news: China appears to be experiencing a rebound in new cases and the onset of the dreaded second wave, although it is still early to determine if there is a sufficiently high number of new cases for Beijing to seek a renewed shuttering of the economy (it is unlikely China will pursue this option until it is again too late and the real number of cases has soared). In any case this dynamic has to be watched closely. An alarming trend is asymptomatic cases have outnumbered confirmed cases recently with expanded testing.

Third, the world succumbs to an extended game of suppression. This scenario means that the world plays a protracted game of whack-a-mole with the virus, stamping out outbreaks here and there until a vaccine can be produced. This is the best option, but also the longest and most complicated. Some companies such as Google understand this. Google Says Most Of Its Employees Will Likely Work Remotely Through End of Year

How would it work?

Existing vaccines work by providing the body with inactivated or fragmented viruses, allowing the immune system to prep its defenses ahead of time. Vaccines essentially give the immune system a crash course in recognizing and rallying defenses against disease-causing microbes like bacteria or viruses.

By contrast, Moderna’s vaccine comprises a sliver of SARS-CoV-2’s genetic material—its RNA. The idea is that the body can use this sliver to build its own viral fragments, which would then form the basis of the immune system’s preparations. This approach works in animals, but is unproven in humans.

Moderna Therapeutics, a biotech company based in Cambridge, Mass., has shipped the first batches of its COVID-19 vaccine. The vaccine was created just 42 days after the genetic sequence of the COVID_19 virus, called SARS-CoV-2, was released by Chinese researchers in mid-January. The first vials were sent to the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Bethesda, MD, which will ready the vaccine for human testing.

NIH scientists also began testing an antiviral drug called remdesivir that had been developed for Ebola, on a patient infected with SARS-CoV-2. The trial is the first to test a drug for treating COVID-19, and will be led by a team at the University of Nebraska Medical Center. The first patient to volunteer for the ground-breaking study is a passenger who was brought back to the US after testing positive for the disease aboard the Diamond Princess. Others diagnosed with COVID-19 who have been hospitalized will also be part of the study.

Moderna’s vaccine against COVID-19 was developed in record time because it’s based on a relatively new genetic method that does not require growing huge amounts of virus. Instead, the vaccine is packed with mRNA, the genetic material that comes from DNA and makes proteins. Moderna loads its vaccine with mRNA that codes for the right coronavirus proteins which then get injected into the body. Immune cells in the lymph nodes can process that mRNA and start making the protein in just the right way for other immune cells to recognize and mark them for destruction.

By contrast, French scientists are trying to modify the existing measles vaccine using fragments of the new coronavirus. The advantage of that is that if we needed hundreds of doses tomorrow, a lot of plants in the world know how to do it.

No matter which strategy is faster, the consensus estimate is that it will take 12 to 18 months to develop a proven vaccine, and then longer still to make it, ship it, and inject it into people’s arms.

How will this pandemic end?

It’s likely, then, that the new coronavirus will be a lingering part of life for at least a year, if not much longer. If the current round of social-distancing measures works, the pandemic may ebb enough for things to return to a semblance of normalcy. Offices could fill and bars could bustle. Schools could reopen and friends could reunite. But as the status quo returns, so too will the virus. This virus has no memory. But this doesn’t mean that society must be on continuous lockdown until 2022. But we need to be prepared to do multiple periods of social distancing.

Arcus believes that next waves could be at a smaller amplitude with lower mortality rate potential compared to the current first wave. This is due to

(1) strong risk awareness among stakeholders;

(2) faster government response potential at the infection tipping point; and

(3) enhanced risk manual at the containment stage.

However, even a substantially reduced amplitude of wave 2 (and 3 and 4), suggest that ongoing economic shutdowns will be recurring feature of life for quarters if not years.

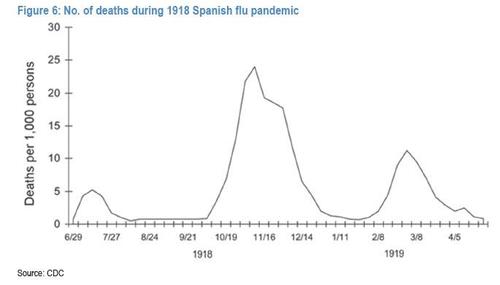

The amplitude could be higher, however, a la the Spanish Flu pandemic, if it turns out that the life cycle of the coronavirus is far longer than assumed.

The bottom line

As Minneapolis Fed chief and former Goldman and PIMCO staffer, Neel Kashkari, stated on CBS’s “Face the Nation”: “Without an effective therapy or a vaccine for the novel coronavirus, economies could face 18 months of “rolling shutdowns” as the outbreak recedes and flares up again. We’re looking around the world and see that as they relax the economic controls, the virus flares back up again. We could have these waves of flareups, controls, flareups and controls until we actually get a therapy or a vaccine. I think we should all be focusing on an 18-month strategy for our health care system and our economy.”

Kashkari warned that “this could be a long hard road that we have ahead of us until we get either to an effective therapy or a vaccine. It’s hard for me to see a V-shaped recovery under that scenario,” he said.

The bottom line, and somewhat counterintuitively, the sooner the world declares victory against Covid, the faster the general population will rush back into “social un-distancing”, sparking new case clusters as the infection restarts from scratch, forcing authorities to re-establish social distancing once again, and so on, as the entire process repeats from square one. Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), also expressed concern about the risks if economies open up prematurely.