Arcus Patient Safety Report: Patient safety practices and management challenges within healthcare organizations. The healthcare industry’s emphasis on improving patient safety has increased in recent years. From the steady rise of hospital-acquired infections to infants receiving blood thinner, a variety of trends and events have thrust the issue into the public spotlight.

Disconnect between how patient safety is discussed and how it is actually defined. Many hospitals seem to recognize the need for multifaceted change for improving patient safety. Internal discussions in these hospitals consistently identify different requirements, including a better-integrated information technology, greater physician involvement, better communication between physicians and nurses, no-blame culture, etc. Yet when we examine what these hospitals actually do as they develop and implement specific patient safety initiatives, a major disconnect becomes evident. Only a few of these components are targeted by initiatives. Typically patient safety efforts focus narrowly on a few organizational components, such as specific clinical practices or outcomes, and even these efforts are not consistent with one another.

Patient Safety Indicators: safety gains and quality

Despite advances in patient safety processes and the proliferation of safety literature touting the importance of everything from public reporting to hand hygiene, however, some recent studies suggest that safety gains are spotty and quality remains inconsistent. With safety issues not only endangering patients but also threatening providers’ bottom lines through longer lengths of stay and higher costs, healthcare management has plenty of motivation to keep patient safety at the top of their priority lists.

Participation limited to a few people playing traditional roles. Generally speaking, patient safety initiatives appear to be initiated and implemented by a small group of people with formal responsibilities for patient safety-related issues (e.g., pharmacy director, vice president, risk management) and informal patient safety champions. Often this group has insufficient authority to tackle issues that cut across departmental boundaries. Although senior leaders express support of these efforts, they are often far removed from the patient safety management process and leave important choices about how change is defined and implemented to mid-level administrators. In many hospitals, there is little evidence that senior, influential representatives from the medical staff, nursing, pharmacy, and legal counsel work together as a guiding coalition.

Absence of dedicated support structures for implementing change. Many hospitals continue to rely on existing structures and mechanisms to implement patient safety initiatives, even when the goals are expressed in terms of significant organization-wide changes. Few attempts, if any, are made to redefine the current responsibilities of individuals and groups engaged in patient safety initiatives or to provide additional resources to support the implementation effort.

Often hospitals rely on committees that are already in place, such as the pharmacy and therapeutic committees, to review progress on implementing the initiative, thereby causing the pace of implementation to be constrained by meeting schedules. The error-reporting initiative represents only one isolated item in an already-crowded agenda of quality and safety issues that are not addressed in an integrated fashion. To encourage health care workers to report medication errors, hospitals implement a few narrowly focused tactics—such as disseminating memos and newsletters, posting signs and notices, giving presentations at meetings, and simplifying the reporting form—which are also typically disconnected from one another.

Inability to sustain change in patient safety practices. In many hospitals, significant increases in error reporting are observed during the first 12 months of an initiative, with declines in the rates of increase thereafter. Key informants from these hospitals point to different reasons for the slowdown. A common theme, however, is that initiatives continue to depend significantly on a few individuals for sustaining its momentum, and therefore are continually vulnerable to additional work demands placed upon these individuals, such as preparing for accreditation reviews

Hardened employee skepticism about the organizational call for change. When change is defined in transformational terms, the expectations of employees are raised, and many want to participate enthusiastically in the proposed change. But when the implementation is characterized by inconsistencies, the process can lead to increased skepticism, not just toward the initiative at hand, but future initiatives as well. In some cases, we observed that hospital leaders espouse a blame-free culture, even as nurses who report errors continue to be “written up.” Indeed, in many hospitals, the forms used for reporting errors continue to list “human performance deficit” as one likely cause, and “human performance deficit” remains among the most commonly identified causes of medication errors. Some nurses respond to new initiatives by reporting more errors, only to find that the same errors continued to occur, so they stop reporting.

Inevitable frustration of patient safety champions. Across hospitals a number of patient safety champions who exist played an important catalytic role in initiating and implementing the error-reporting initiative. These physicians, nurses, and pharmacists participate actively in new initiatives from their inception. Interviews indicate that they had high expectations and enthusiasm for initiatives. Few years into an effort, however, some of them express frustration with the scope of change, pace of progress, and lack of support from senior leaders. Several cases where patient safety champions are overwhelmed by poorly conceived and executed initiatives.

“Mis-learning” by organizational members. Mismanaged change can actually make patient safety worse. Take, for example, the previously described situation where nurses stopped reporting when the medication errors they uncovered were not corrected. In one hospital, these nurses went so far as to set up a “work-around” (e.g., a hotline to the pharmacy for reporting missing medication); they now call the pharmacy to obtain missing medication, rather than report these incidents as errors.

Healthcare organizations are prepared to address patient safety issues but can do more. In an overall self-assessment as to where their organization stands with respect to addressing patient safety, respondents report an average score of three on a five-point scale. In this scale, one represents “not at all prepared” and five is “completely prepared.” By revenue size, larger organizations are slightly more likely than small organizations to be prepared for patient safety (3.5 compared with 3). Respondents who work for hospitals that are part of a multi- hospital system are more likely to believe their organization is prepared to addressing patient safety than are respondents who work at stand-alone hospitals.

There are clear barriers for implementation of patient safety programs. It begins with inadequate ownership of patient safety. In most organizations, the patient safety budget is a subset of each department. So there is resistance to an enterprise wide program for implementation of patient safety. There is a gap in analysis of ROI for investments in patient safety because of lack of national benchmarks. MD resistance is often mentioned as a key barrier to implementation of programs. Vendor products, especially in IT, are a substantial gap. Several organizations now have patient safety related IT infrastructure developed in-house.

Interestingly, survey respondents consistently rated their organizations as fairly well prepared to address patient safety issues. The rating in the 3.00 to 4.00 range indicates that there is still some work to do to enhance patient safety, yet respondents believe their organizations are attentive to the issue.

Staffing shortages have an impact on patient safety but are not yet a crisis. Respondents were asked to identify the impact they thought staffing shortages would have on patient safety, using a scale of one (no impact) to five (tremendous impact). The average score was 3, suggesting a moderate level of impact. Additionally, respondents do not, for the most part, believe that technology plays a significant role in alleviating staffing shortages. When asked to select from a number of patient safety issues that could be addressed by technology, respondents were least likely to select staffing shortages.

Physicians are more likely to believe that staffing shortages will impact patient safety than are CIOs.Those working at stand-alone hospitals are more likely to identify that staffing shortages will affect patient safety than are those working at hospitals that are part of a multi- hospital system or network. Finally, organizations with budgets of $200 million or less are more likely to indicate that staffing shortages will affect patient safety, than are those who work for larger organizations. Although there has been much concern expressed about staffing shortages greatly impacting patient safety, the survey respondents ranked other issues ahead of staffing. Not unexpectedly, clinicians were more concerned about staffing shortages.

When the data are evaluated more closely by demographic variables such as organization type and size, subtle differences appear. While organizations of all sizes (revenue) appear to rank the data in a similar manner to that of the entire sample, an analysis of responses suggests that the factor that most affects the decision to implement patient safety tools differs by type of organization.

Survey respondents working at hospitals that are part of a multi- hospital system or network are most likely to report that the organization’s strategic mission affects the decision to implement patient safety tools. Respondents working at the other facility types are most likely to report that the strategic mission has the most impact on the decision to implement patient safety tools.

Strategic mission and accreditation are driving patient safety initiatives. Interestingly, the government plays a relatively minor role today in driving patient safety initiatives. Hospitals themselves are taking the initiative to address patient safety.

Patient safety initiatives are broadly established, and while leadership for these efforts varies, nurses and physicians play a central role. Nearly all of the individuals responding to this survey, report that their organization has implemented a patient safety initiative. Among traditional job titles, nurses are named slightly more often than physicians as the leader of patient safety initiatives in the organizations represented in this sample. Chief nursing executives and patient safety officers, a relatively new role in healthcare, each were identified by a fifth of respondents as having primary responsibility for leading the patient safety initiative in their organization. A fifth of respondents indicated that the risk management department is responsible for patient safety, and a sixth said that the chief medical officer has primary responsibility. Only six percent of survey respondents indicated that their chief executive officer has this responsibility.

Not all organizations have formed a formal committee to address patient safety. Eleven percent of respondents indicate that their organization has not yet established a patient safety committee. The universal existence of patient safety initiatives indicates that patient safety is truly a top-of-mind issue for organizations and that they are taking steps to address it. At the same time, the diversity of leadership of these initiatives shows that the organizations are in the beginning stages of establishing a structure to manage patient safety and are currently deciding on priorities.

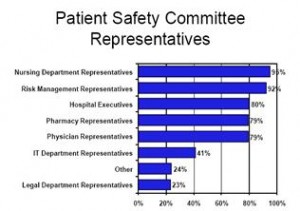

Patient safety committees are broadly representative of hospital departments. Nursing is most likely to be represented, while the information technology and legal departments are the least likely to be represented. Survey data suggest that patient safety committees have a broad range of representation across facility departments, with most reporting that either a physician or a nurse sits on the patient safety committee. Over two-thirds of the respondents indicate that individuals from at least five departments sit on the patient safety committee; only five percent have representation from two or fewer departments.

Among those respondents who reported that their organization has a patient safety committee, nursing department representatives are most likely to sit on the patient safety committee, followed by employees from the risk management department. Patient safety committees are also likely to include hospital executives, pharmacy representatives and physicians. Conversely, less than half of the respondents in this survey indicated that members of the IT department or legal department sat on the patient safety committee.

The strategic mission of healthcare organizations considerations drives decisions to implement patient safety tools. Respondents in this survey were most likely to identify that the strategic mission of their organization led to the decision to implement patient safety tools. Two-thirds of the respondents reported that the Safer Healthcare Now initiative is one of the top factors that had an impact on their organization’s decision to implement patient safety tools.